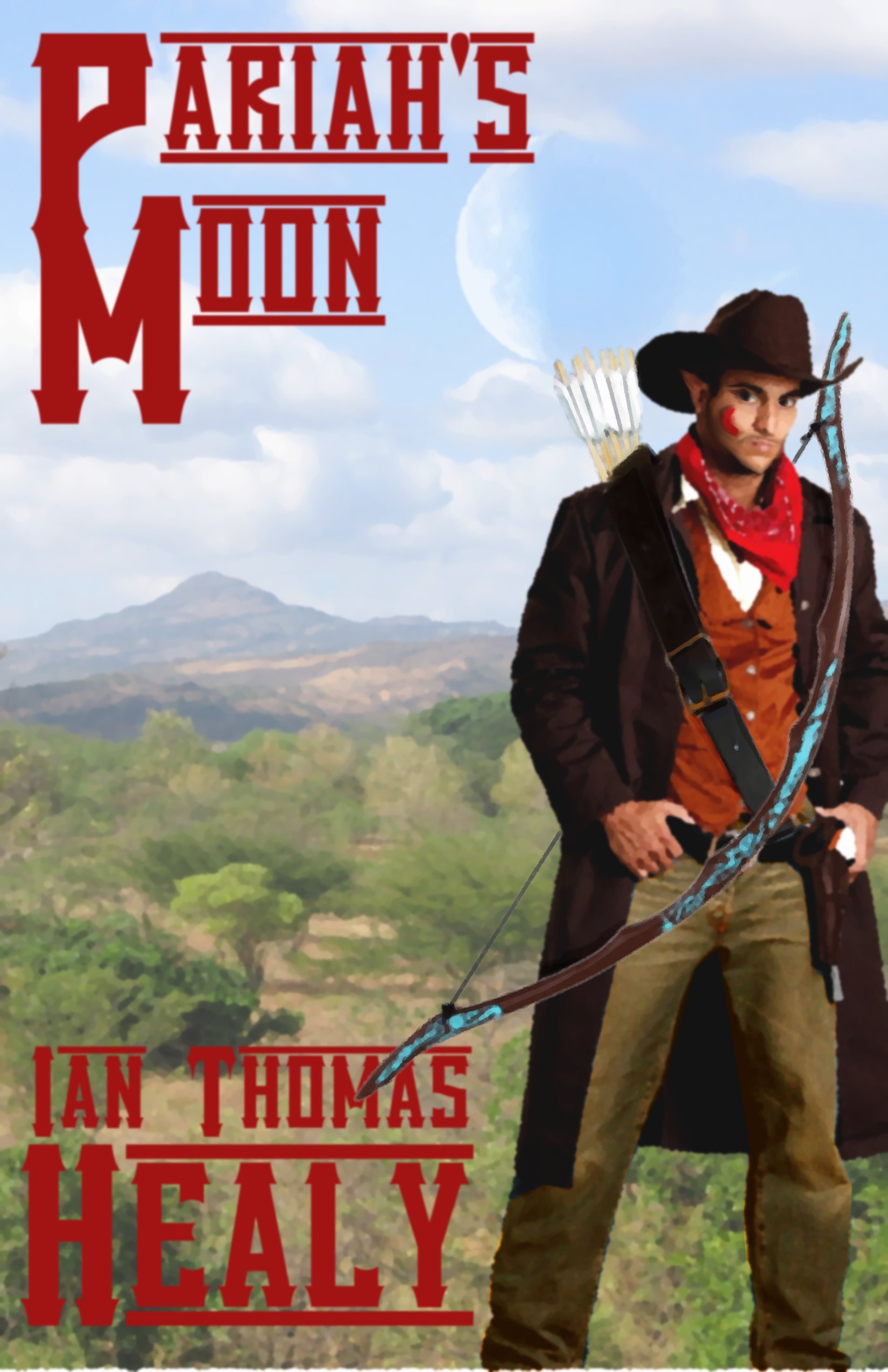

The largest dog howled a war cry and the others lunged forward. Cecily screamed. She turned, took two steps and tripped over sagebrush. An arrow whizzed over her head, then another and another and another. All four dogs stumbled and fell.

Uncle North! Thank the winter brothers for Uncle North! [Formatting point: Later on you italicize thoughts. Make sure you’re consistent.]

Cecily pushed herself up and ran. She jumped over sagebrush and dodged juniper trees. She heard the dogs stagger to their feet, heard their howls, heard their paws thumping the ground. [Your repeated “heards” are slowing down the pacing of this moment.]

Then there were howls in front of her and Cecily realized where the four missing dogs were. [I thought the dogs had been shot from your opening sentences. You should clarify that they were not. Dogs are generally sure-footed animals, and for all four to stumble and fall together sounds contrived.]

She stumbled to a stop and stared at the dogs. She was surrounded. [Are these wild dogs or trained? I realize that’s probably covered outside this excerpt, but if they’re trained and have been ordered to hunt her down, I think they’d probably attack right away.]

I am going to die, I am going to die.

For some reason that realization gave her a sliver of courage and she remembered her hunting knife. [This has an emotional disconnect for me. How does her realization that she’s going to die suddenly make her courageous?] Her gloved hands fumbled for it and somehow managed to remove the blade from its sheath. She adjusted her grip on the knife and watched as the dogs circled her. Why didn’t they attack? [I’m glad to see that the character is asking herself the same question I am.]

Uncle North shot another arrow and it lodged in a dog’s back. The dog staggered and turned to look at Uncle North who was perched on the ridge. [This doesn’t work for me. A dog isn’t going to immediately look at the source of an arrow. In the dog’s mind, he’s find, and then he’s hurt. He’s going to whimper and try to snap at the thing stuck in his back. He doesn’t know it’s an arrow, or that it was shot at him from a distance. It’s just there.] The dog shook its head and turned back to Cecily. [And again, this is not a natural doggie response to an injury. If these are unnatural creatures, these might be adequate actions, but otherwise they don’t work.] Uncle North shot the dog again and hit its leg. The beast’s eyes flashed. [Like a flashbulb going off or is this a metaphor? I’m unsure these are dogs instead of demonic beasts (or something). You might clarify it a little more.] It snarled and turned and raced towards the ridge. [I know I keep bringing this up, but the dog has cornered prey right in front of it. Why is it turning to go after the distant man? Dogs don’t understand cause and effect.]

Instinctively Cecily bolted towards the hole it left. A dog on her left lunged to cut her off and she slashed at it. If she reached the mountain, she could climb to safety. [Is the dog going to hamstring her? How large are these beasts? A small dog would try to bite through her ankle, to hobble her and make her easier to knock down. A large dog would just try to bear her down and tear out her throat, intestines, or other soft tissues.

Also, unless this mountain is a sheer cliff face, dogs can climb it.]

Teeth sank into Cecily’s pant leg. She stumbled head first and flipped over. Her accidental summersault pulled her leather trousers from the beast’s mouth and somehow she was on her feet again [Don’t “somehow” it, show what happened.], racing blindly ahead. She almost ran into a massive boulder barring her path. No time to go around. She dropped her knife, found hand holds, and climbed the rock. It was fifteen feet high and much wider. She crawled to the middle, gasping for breath. Ten feet of rock on all sides, fifteen feet in the air. [This rock would have to have sheer sides for a dog not to be able to get onto it. Is it a natural rock or a carved piece of stone?]

She was safe.

A mangled scream, a human scream, sliced the air. Cecily lifted her head, saw Uncle North on the mountain ledge, clutching his leg. The dog with an arrow in its back slid down the mountain face. It hit the ground, crouched then sprang. It pushed off the vertical mountain halfway up and propelled itself just high enough to clamp down on Uncle North’s foot before it fell to the ground, pulling Uncle North with it.

Cecily’s arms buckled. That ledge was twenty-five feet in the air.

Cecily screamed as a dog jumped onto her rock. And then another. And another. They advanced. [These three 2- and 3-word sentences slow your pacing down significantly. In this case, the three brief sentences add nothing positive to your narration. I think if you were to expand them just a little, you would improve the narration without hurting the feel. Are the dogs panting? Drooling? How do their claws sound on the rock? Are they advancing to kill her?] She crawled away from them. Her hand slipped off the edge of the rock and she almost fell. She looked down. The others were waiting for her below. There was nowhere to go.

[You’ve got a basic structure of an action scene here, and what it’s really crying out for is some better pacing and stronger description. Every time you end a sentence, a reader will pause briefly (they won’t really notice, but read it aloud and you’ll see what I mean). Every time you end a paragraph, the reader pauses even longer. You have a lot of short sentences and single-sentence paragraphs in this excerpt, and that’s serving to bring your pacing to a crawl when the scene should really have a lot faster pacing.

You can add richer language and description to an action scene without harming the pacing. You have both dogs and Cecily stumbling. She crawls a couple times. I have no picture of these dogs or the setting from your excerpt. Again, this may be earlier in the narrative before this excerpt, but you could stand to give a little more information about it here.

Since you’re narrating in close POV, you could stand to add a little more emotional content as well. Cecily is terrified. Anybody would be – who wants to be torn apart by dogs? We’re in her head. Let us feel what she’s feeling.

Thanks for participating!]